Christina V. Cedillo

Panel 691: Scholarly Journal Publishing with a Disability-Centered Approach

Sunday, 8 January 2023; 10:15 AM - 11:30 AM PST

Download a PDF of the slides here: SLIDES

Download a PDF of this talk here: TALK

----------

[Slide 1] Hello, I’m coming to you from Houston Texas, which sits on traditional Karankawa, Sana, and Atakapa land. Before I start, I want to offer a content warning for some of the images I share, and offer a bit of warning because as usual, I’ll be addressing this theme in my typical roundabout way. [Slide 2] For now, I want to begin with a story about the whitestream character of publishing, explain how racism and ableism are so fundamentally entwined in everyday life and in publishing, and conclude by offering some quasi-suggestions from the perspective of a crip researcher-editor in moving forward.

[Slide 3] One way to start this story about the endemic whitestreamness of publishing is to go back to 2020. In that year, Paula Chakravartty, Rachel Kuo, Victoria Grubbs, and Charlton McIlwain published the article “#CommunicationSoWhite.” According to the authors, they wrote the article seeking to expose the (to be frank, unsurprising) over-representation of white scholars in academic publishing. They state, “As part of an ongoing movement to decenter White masculinity as the normative core of scholarly inquiry, this paper is meant as a preliminary intervention. By coding and analyzing the racial composition of primary authors of both articles and citations in journals between 1990–2016, we find that non-White scholars continue to be underrepresented in publication rates, citation rates, and editorial positions in communication studies” (254). As someone working in rhetoric, a discipline that overlaps and/or is part of communication, depending on who you’re talking to, the article was both welcome but also not shocking. And yet, when this essay was published, it was not without controversy. Even as some disputed the racism of the discipline and the academy at large, scholars of color took up the #CommunicationSoWhite hashtag on Twitter to share their personal experiences with racism, or should I say of being targeted by racism because we know racism isn’t just something that is—it is something that is enacted even and especially when it is structural.

Chakravartty, Kuo, Grubbs, and McIlwain concluded by suggesting ways forward, stating that it is important to avoid essentialism and tokenism, that we must all interrogate our citational practices and “apply pressure everywhere” (262), meaning change how we compose our syllabi, reading lists, qualifying exams, and pedagogies. After all, the point is not to simply increasing citational representation on the surface level but “attending to structures of power embedded within knowledge production” (ibid.). It is all to easy to cite the right names and act the role of a good ally; it is quite another to value the knowledge springing forth from marginalized communities and experiences as equally authoritative, or even more so than whitestream sources, since marginalized perspectives perceive realities that the privileged position never has to realize exist, let alone acknowledge. [Slide 4] As Eric Darnell Pritchard argues in “‘When You Know Better, Do Better’: Honoring Intellectual and Emotional Labor Through Diligent Accountability Practices,” a guest blog published on Carmen Kynard’s blog Education, Liberation & Black Radical Traditions for the 21st Century, it’s going to take some major changes at all levels to get to the place of radical difference at the publishing level. From CFPs that omit those ostensibly being centered, to students asking for marginalized scholars advice on reading only to exclude them from their committees, to being worn out from being the diversity on Equity and Inclusion work that never goes anywhere, Pritchard states, “I want to be unequivocal in saying that my point here is an indictment of and call for all to do better.” It’s going to take all of us, not just us marginalized folks, because the truth is, we literally live in different worlds. You see, for many white colleagues, “#CommunicationSoWhite” marked a startling new call to antiracist action rather than yet another plea against invisibilization. As Robert Mejia (2020) argued in the introduction to a forum on communication and the politics of survival, believing that the call to action began with this article’s publication was proof of the discipline’s erasure of the many scholars of color who have consistently written about racism and other inequities in the academy and beyond. Thus, I began by saying this was one way to start this story because this story’s been written for a very long time but not everyone’s been paying attention.

[Slide 5] So now, some may be asking why I began with a story about #CommunicationSoWhite when this is a panel on disability and publishing. What do these things have to do with each other? Once again, whitestream academia would say they are separate concerns, but many of us live lives that tell us they are inseparable, as corroborated by history. We can begin with that word, “whitestream,” which for me as a multiply marginalized person is a much more resonant concept than mainstream. Sandy Grande writes in her critiques of whitestream feminism that it “is not only dominated by white women but also principally structured on the basis of white, middle-class experience; a discourse that serves their ethno-political interests and capital investments” (331). Jay Dolmage also reminds us that “the normate subject is white, male, straight, upper middle class; the normal body is his, profoundly and impossibly unmarked and ‘able.’ On the page, this subject and his body translate as error-free, straight and logical prose…” (110). The mainstream is white, but that is not only about race; whiteness is also about being nondisabled, affluent, cis, straight, reliant on colonial structures that dare to taxonomize life based on the social lottery of privilege or its denial. It also assumes that academics know more about particular topics than the people who live them, with academics writing about their own experiences viewed as less authoritative than the well-known scholars who theorize the crap out of oppressions because they have no first-hand knowledge to accompany their research. Everyone needs to recognize and combat ableism, but everyone also needs to call out how people of color are disabled by the same system.

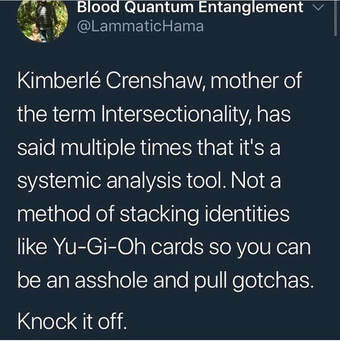

When we look at the histories of race and disability, we really mean the histories of racism and ableism, because in a colonial system, race is a schematic of valuating life according to the assumed potential to strive for reason and greatness and disability is the means of doing so. Race may be a social construct but the violence targeting our bodies are material and real. Members of minoritized communities are more likely to become disabled or have their disabilities misdiagnosed or ignored. In school, Black students with disabilities are more likely to be labeled disruptive or defiant (see Erevelles, 2014). On the other hand, disability typically indicates some kind of physical impairment even when that part of the body happens to be the mind, but it can never be unlinked from social stigma and prejudiced views about what we can do, what dignity and joy we deserve, and how much we are worth in terms of cost vs. labor as has been determined according to racial hierarchies. We should not render these marginalized identities fungible in terms of experience. As Kimberlé Crenshaw writes, “The problem with identity politics is not that it fails to transcend difference, as some critics charge, but rather the opposite—that it frequently conflates or ignores intragroup differences” (1242). Indeed, it is one part of racism to assume one’s disability means one knows what it means to be racialized. However, for those of us who are racialized and disabled, it becomes clear that there are points of resonance. We find that we are already suspect because our work isn’t assumed to have the same universal application as that of our white colleagues, and if our disability isn’t ignored altogether, then it becomes another way to background our work. After all, what does a “very limited” racialized and disabled perspective have to offer, right? When you consider that over ¼ of the U.S. population is disabled (U.S. Census, 2022), and this does not include those who don’t identify as disabled or those who will become disabled due to illness or age, this perspective has much to offer. Disabled people make up the largest marginalized population in the US, and the multiply marginalized perspective reveals what happens when disability intersects with other forms of oppression.

[Slide 6] Racism and ableism help create one another; difference is constructed through the demonization of disability—just think about how often the categories used to classify disabled people are used to indicate a lack of sense, intelligence, or potential—while disability became associated with race through the denigration of racialized bodies. [Slide 7] In fact, white disability is often deployed to regulated racialized disability by suggesting that adding race is a distraction in discussions about disability rights. But that’s how colonial oppression works: it makes struggles seem unrelated. And that’s how academic discourses function to bolster that system: we are expected to handle topics mono-dimensionally rather than intersectionally, interactively, and publishing rewards those who do this for producing research that is somehow more applicable for erasing myriad factors and circumstances. In this way, social justice movements and orientations can promote and reproduce the very conditions they contest if anti-oppression discourse is prioritized over spatial and material transformation which, as a goal, reveals whose perspectives can illuminate our research from multiple angles.

So with all of this in mind, then, what does it mean for me to use a disability-centered approach in publishing? I want to turn briefly to a 2020 article by Cruz Medina and Perla Luna titled “‘Publishing Is Mystical: The Latinx Caucus Bibliography, Top-Tier Journals, and Minority Scholarship.” They begin by citing the same blog by Pritchard, as they (Pritchard) draw attention to the inequities of publishing, including being asked to review work for journals that will then reject work by the same scholars of color they count on to review (304). I want to express rage on that front, personally, as well as vent a bit as a disabled researcher-scholar-editor, knowing how the same “quality venues” will publish nondisabled scholars sneezing in the direction of disability studies because their writing style looks the part or they make it less uncomfortable by dressing it up in the theory of the day even if it lacks the experience or the soul. As I have also tried to make clear here, Medina and Luna explain that citational politics matter since scholarship reifies dominant attitudes in the form of pedagogies, organizational practices, and public intellectualism (Medina, 2020). When whitestream scholars speak over BIPOC and disabled scholars, ignoring our work or refusing to make room for us, they affect the retention and promotion of faculty and students and influence how we are perceived by the general public. Stated plainly, what—and who—receives public attention reflects and reifies society’s norms, contributing to their persistence in the forms of erasure, financial and physical precarity, and even loss of life. And this, ultimately, is what it means to center material and spatial vulnerability as well as expertise. In the introduction to Black Disability Politics, Sami Schalk explains that “Black disability politics are often performed in solidarity with disabled people writ large, but the articulation and enactment of Black disability politics do not necessarily center traditional disability rights language and approaches, such as disability pride or civil rights inclusion; instead, they prioritize an understanding of disability within the context of white supremacy” (5). As Schalk says, it means to confront “the whiteness and racism of the disability rights movement and disability studies as a field” and acknowledge that disability politics in Black and other minoritized communities may be enacted differently than they are in whitestream disability movements (6). So for me, a disability-centered approach is an anti-white supremacy approach is an anti-colonial approach is a culturally-sustaining approach.

[Slide 8] Usually, when I do workshops and presentations, people want a checklist of things they can do to make their own praxes more antiracist, disability-friendly, and so on. But I want to be very clear that before you can enact anything I share, one has to do the work of looking into the long history of oppression that makes people like me loath to just give people some easy tips so they can do the bare minimum and yet be seen as the vanguard. I can tell you that all of our journal’s editors are queer disabled people, including folks like Ada Hubrig, Vyshali, and Cody Jackson, who are not only amazing scholars but people who are about that life and are committed to disabled, racial, queer, and trans justice because yes, “Nothing about us without us,” but we will not have our identities parceled out. This makeup happened because we know each other, work together; there is love and respect there. I can tell you that if someone is looking to diversify their venue but don’t actually know diverse people, they should ask themselves why. I can tell you that our journal began as a response to racist, ableist venues who would rather gatekeep than help less privileged writers who lack mentorship or support. Some venues pride themselves in publishing only “the best,” as one editor wrote back to me when I was right out of grad school, having buried two parents and a marriage while contending with depression and anxiety. As editors, we do NOT diagnose people or make assumptions about their backgrounds, but people often ask me how we know why we should help them—a disability approach doesn’t demand disclosure; we extend support that makes room for disability and care, including our own. I can tell you that you need to be ready to be a squeaky wheel, a pain in the ass, and push back against talk of standards and rigor and innovation and originality when oftentimes, the so-called new conversations were already had in other circles and sometimes, the same argument needs to be made again and again until privileged folks are willing to listen. We need to humanize publishing, make ourselves accountable to one another and know each other as human beings. I can tell you that we work in crip time, as our bodies allow, while also recognizing that people have due dates to manage because institutions make impositions on people’s time even in the midst of deadly pandemics. Being online and independent makes this easier since we don’t have print issues to get out at set times. (Just something for authors to think about!) And finally, I can tell you that being crip means we do this DIY punk rock style, making our own spaces that are “lo-fi,” trying new things, starting new venues, hosting conversations and publications that do what we want them to do in an academy that often wants us to write and live like it’s 1920. But how you find your own disability-centered approach will be up to each person or team. Approaches shouldn’t be the same anyway because we are not all the same and they reflect who we are. But I believe we will keep cripping, changing, challenging, and pushing. [Slide 9] And so, I want to close with some words by Alice Wong: “I often wonder how disabled people will survive in a post-apocalyptic world… What I do know is that disabled people are creatures of adaptation that design and build worlds that work for them. The skills that we have reimagining/hacking/surviving hostile ableist environments would serve us well in any dystopian future.”

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, October 28). Disability impacts all of us. CDC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html

Chakravartty, P., Kuo, R., Grubbs, V., & McIlwain, C. (2018). #CommunicationSoWhite. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), pp. 1241-1299.

Dolmage, J. (2012). Writing against normal. In K. L. Arola & A. F. Wysocki (Eds.), Composing media composing embodiment (pp. 164-173). Utah State Press.

Erevelles, N. (2014). Crippin’ Jim Crow: Disability, dis-location, and the school-to-prison pipeline. In L. Ben-Moshe (Ed.), Disability incarcerated (pp. 81-99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Grande, S. (2003). Whitestream feminism and the colonialist project: A review of contemporary feminist pedagogy and praxis. Educational Theory, 53(3), 329-346.

Medina, C., & Luna, P. (2020). “Publishing is mystical”: The Latinx Caucus bibliography, top-tier journals, and minority scholarship. Rhetoric Review, 39(3), 303-316.

Mejia, R. (2020) Forum introduction: Communication and the politics of survival. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 17(4), 360-368, DOI: 10.1080/14791420.2020.1829657

Pritchard. E. D. (2019, July 8). “When you know better, do better”: Honoring intellectual and emotional labor through diligent accountability practices. Education, Liberation & Black Radical Traditions for the 21st Century: Carmen Kynard's Teaching & Research Site on Race, Writing, and the Classroom. http://carmenkynard.org/featured-scholar-eric-darnell-pritchard-when-you-know-better-do-better-honoring-intellectual-and-emotional-labor-through-diligent-accountability-practices/

Schalk, S. (2022). Black disability politics. Duke University Press.

Wong, A. The rise and fall of the plastic straw: Sucking in Crip defiance. Catalyst: Feminism, theory, technoscience, 5(1), 1-12. https://catalystjournal.org/index.php/catalyst/article/view/30435/24783